|

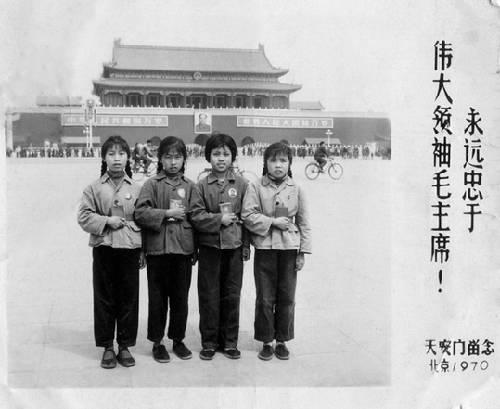

| A 1970 picture of four girls, each holding a small red book of late Chairman Mao Zedong, in Tian'anmen Square. |

"I hope my photography and writing can arouse public attention about these groups' circumstances and help improve their lives."

It gives Hei a strong sense of achievement to see impoverished interviewees receive donations for their hospital bills or job offers after people see his photos.

"My photography is not the kind of art that belongs to just a small circle. I don't want to indulge in self-admiration of my photos at home together with a few friends," Hei says.

"I'm presenting life and social changes through my photos and I want to get my observations across to the masses."

The 49-year-old has published more than 20 photo collections, most of them about "people": 100 farmers, 100 Shaolin monks, 100 Tibetan people, and 100 inhabitants of border areas.

Hei says his choice of subject is born out of his curiosity, but it always turns out to be of public concern as well.

He says he lived at Shaolin Temple because he wanted to know whether it's true that monks don't eat meat. Of course, he was also able to offer readers of his book, Shaolin Monks, an honest exploration of Buddhism in China.

He went to the small village of Xinyaozi in his childhood province of Shaanxi more than 30 times, from 1996 to 2004, to create a book about the transformation of the 100-year-old village. Bumpy journeys on tractors and sleeping in a cold, deserted room didn't bother him. The Beijing-based photographer enjoyed the escape from city life and made good friends with the simple, honest villagers.

|  |

Three injured in plane's failed take-off in NE China | Pictures

Three injured in plane's failed take-off in NE China | Pictures

![]()