The ancient Chinese invention of wooden movable-type printing is marching forward in the village of Dongyuan, Wenzhou.

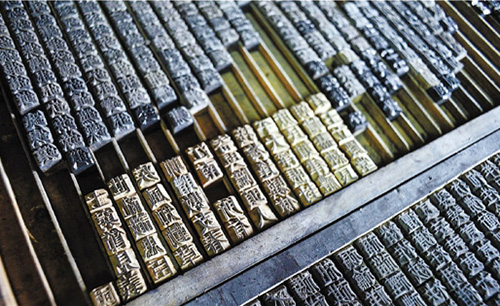

One-centimeter wooden cubes are arrayed in a jet-black rectangular frame. A reversed Chinese character is sculpted on each cube. Repeatedly smeared with ink for many years, these pale yellow matrices have been dyed nearly dark enough to match the ink itself.

Once the matrices are inked, a high-quality Chinese art paper is placed on top of them. The paper is then brushed and smoothed until the ink marks appear. Once the paper is removed, the page is printed with vertical, traditional Chinese characters. Assembling and binding such pages together produces a book.

Wang Chaohui, 60, inherited the traditional trade from his grandfather. In Dongyuan, there are around 20 technicians like Wang. Thanks to the strong culture and large demand for genealogy records, this technique has been successfully handed down from one generation to the next.

According to historical data, southern Zhejiang and northern Fujian provinces used to be migrating societies. Living a vagrant lifestyle and traveling in groups, people in the region easily formed a strong sense of clan. Genealogy, therefore, is an important concept in Wenzhou.

Over the past decades, Wang has sculpted over 10,000 wooden movable-type cubes every year. He has also used nearly 100 engraving knives and over 7,000 sheets of art paper.

Wang explained that geneaology records generally consist of four or five volumes. They are revised and updated every 20 to 30 years, or as frequently as every 10 years in some areas. In terms of cost and operating efficiency, wooden movable-type printing is the best choice for these records.

The only person who could "inherit" the technique from Wang is his 32-year-old son, Wang Jianxin. However, so far, Wang Jianxin has not demonstrated any special skill at the core technique of sculpting. Of the 20 technicians in Dongyuan who are able to work on genealogy revision, not a single one is below 50 years of age.

World's fastest bullet train to start operating next month

World's fastest bullet train to start operating next month Huangluo: China's 'long hair village'

Huangluo: China's 'long hair village' Spectacular bridge with one of the tallest piers in the world

Spectacular bridge with one of the tallest piers in the world Magnificent view of Hukou Waterfall

Magnificent view of Hukou Waterfall A glimpse of Stride 2016 Zhurihe B military drill

A glimpse of Stride 2016 Zhurihe B military drill US Navy chief tours Liaoning aircraft carrier

US Navy chief tours Liaoning aircraft carrier Chinese American woman wins Miss Michigan

Chinese American woman wins Miss Michigan Centenarian couple takes first wedding photos

Centenarian couple takes first wedding photos Traditional Tibetan costumes presented during fashion show

Traditional Tibetan costumes presented during fashion show Top 10 livable Chinese cities

Top 10 livable Chinese cities Top 20 hottest women in the world in 2014

Top 20 hottest women in the world in 2014 Top 10 hardest languages to learn

Top 10 hardest languages to learn China’s Top 10 Unique Bridges, Highways and Roads

China’s Top 10 Unique Bridges, Highways and Roads Sino-US ties will be shaped by interactions

Sino-US ties will be shaped by interactions Human remains, pottery found in China's 4-millennia Dongzhao Ruins

Human remains, pottery found in China's 4-millennia Dongzhao Ruins Olympic team charms HK

Olympic team charms HK Teenagers left traumatized by ‘electroshock therapy’

Teenagers left traumatized by ‘electroshock therapy’Day|Week