Workers fasten electric wires in a rural area in Chuzhou, Anhui province. [SONG WEIXING/FOR CHINA DAILY]

Predicting the end of China has now become a fad. In the past quarter century or so, at least three rounds of "death notifications" on China have been issued: first at the turn of the 1990s and then in the early 2000s, most famously epitomized by Gordan Chang's eye-catching book, The Coming Collapse of China.

Last year, veteran China watcher David Shambaugh joined the rank with his op-ed in The Wall Street Journal, warning about "the coming Chinese crackup" and claiming the "endgame of communist rule in China has now begun".

Unsurprisingly, a sudden U-turn by the prominent Sinologist known for his moderate views sparked an international debate on "China's future", which is exactly the title of his new book.

This time extended arguments are supplied, many of which are more nuanced than the shorter commentary. Nonetheless, the key theme remains: China is on the verge of demise.

To be fair, unlike Chang's much more blunt forecast which proved utterly wrong not once but twice, Shambaugh has been making his case in a smarter way. He avoids to a large extent the embarrassment of being proved wrong. Yet he falls prey to what can be called the trap of "collapsism", which suffers from two symptoms.

First, the central tenet of Shambaugh's case for China's fall focuses on the political, by which he means the one-party rule.

For example, in China's Future he argues that innovation — which he considers the key to China's economic future — can only take off when "substantive political liberalization" takes place. The book underestimates, if not dismisses, China's political system's responsiveness to societal changes.

In this sense, Shambaugh's "collapsism" places inadequate confidence in both the Chinese people and State.

Facts speak otherwise. For instance, the contracting-out system of rural land in China was famously initiated by a group of farmers in a remote village in Anhui province, which turned out to be one of the most successful policy innovations in the 20th century.

It started bottom-up illegally but the State was quick to give it consent at first, then approval and finally assurance and support.

Since the 1990s the contract period has been extended twice, from 15 years to 30 years to unspecified long term, and a specific law passed for the system. This is but one example of social dynamism and State responsiveness in the 30-odd years of China's reform.

Nevertheless, it is enough to show Shambaugh is absolutely correct in directing our attention to the Chinese political system when it comes to pondering the country's future — it is just that in overdoing so, he turns to be a victim of his own success.

The second symptom of Chinese "collapsism", Shambaughian or otherwise, is that it relies on an over-simplified yet long-entrenched dichotomy between authoritarianism and democracy. The associated verdict is simple: democracy lives while authoritarianism dies. There are two problems with this dichotomy.

|

The evolution of J-10 fighter

The evolution of J-10 fighter Top 10 Asian beauties in 2016

Top 10 Asian beauties in 2016 Train rides through blossoms

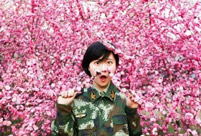

Train rides through blossoms When female soldiers meet flowers

When female soldiers meet flowers North Sea Fleet conducts drill in West Pacific Ocean

North Sea Fleet conducts drill in West Pacific Ocean Old photos record the change of Sichuan over a century

Old photos record the change of Sichuan over a century Breathtaking aerial photos of tulip blossoms in C China

Breathtaking aerial photos of tulip blossoms in C China Horrific: Pit swallows 25 tons of fish overnight

Horrific: Pit swallows 25 tons of fish overnight Police officers learn Wing Chun in E. China

Police officers learn Wing Chun in E. China Top 20 hottest women in the world in 2014

Top 20 hottest women in the world in 2014 Top 10 hardest languages to learn

Top 10 hardest languages to learn 10 Chinese female stars with most beautiful faces

10 Chinese female stars with most beautiful faces China’s Top 10 Unique Bridges, Highways and Roads

China’s Top 10 Unique Bridges, Highways and Roads Groundwater 80% polluted

Groundwater 80% polluted As real estate prices rise, so do risks

As real estate prices rise, so do risks Prostitution plagues China’s budget hotels

Prostitution plagues China’s budget hotels Raising sea tensions serves Pentagon’s ends

Raising sea tensions serves Pentagon’s endsDay|Week