'Jin' named the word of the year by cross-strait netizens

'Jin' named the word of the year by cross-strait netizens Chinese scientific expedition goes to build new Antarctica station

Chinese scientific expedition goes to build new Antarctica station

Chinese naval escort fleet conducts replenishment in Indian Ocean

Chinese naval escort fleet conducts replenishment in Indian Ocean 17th joint patrol of Mekong River to start

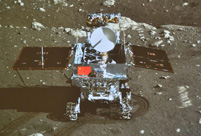

17th joint patrol of Mekong River to start China's moon rover, lander photograph each other

China's moon rover, lander photograph each other Teaming up against polluters

Teaming up against polluters

|

| Han Shuo leaves her home for school as the new semester begins in September. Photo: Li Hao/GT |

Eight-year-old Han Shuo looks no different from any other young child. She is quiet, loves reading, doing origami and watching singing competitions on TV.

However, she never takes part in sports at school, has to be extremely careful when climbing stairs, and when she has nosebleeds, it takes more than three hours to stop.

When she stands, even her ankle-length cotton dress can't hide the fact that her belly has swollen up like a pregnant woman's: her spleen is almost 40 times the normal size.

"She had wanted to become a doctor when she grows up, but the doctor said there's a possibility she won't live past 8 or 9," Han Shuo's father Han Qi said.

Han Shuo, living in Tianjin, was diagnosed with Gaucher's disease in 2009, a genetic disease that makes an enzyme defective and causes a fatty substance to accumulate in cells and organs. In Han's case, it makes her anemic, enlarges her spleen and obstructs her skeletal growth.

Enzyme replacement therapy is the only method to reduce the size of her spleen and keep her blood level stable, but the medicine costs about 2 million yuan ($329,456) per year.

Gaucher's disease is categorized as a "rare disease." According to the World Health Organization, a rare disease is one that affects a small percentage of the population, ranging from 0.65 to 1 in 1,000. However, China does not have a clear definition of a rare disease. Moreover, the medicine developed to treat these diseases - often known as "orphan drugs" - are too expensive for patients, and sometimes not produced because of low profit margins.

Activists are pushing to get these orphan drugs included in national medical insurance and trying to make rare diseases more known to the public. Meanwhile, patients like Han are still faced with a dilemma.

People prepare for upcoming 'Chunyun'

People prepare for upcoming 'Chunyun'  Highlights of Beijing int'l luxury show

Highlights of Beijing int'l luxury show Record of Chinese expressions in 2013

Record of Chinese expressions in 2013 China's moon rover, lander photograph each other

China's moon rover, lander photograph each other 17th joint patrol of Mekong River to start

17th joint patrol of Mekong River to start Spring City Kunming witnesses snowfall

Spring City Kunming witnesses snowfall Heritage of Jinghu, arts of strings

Heritage of Jinghu, arts of strings Weekly Sports Photos

Weekly Sports Photos PLA elite units unveiled

PLA elite units unveiled  China's stealth fighters hold drill over plateau

China's stealth fighters hold drill over plateau Chinese navy hospital ship's mission

Chinese navy hospital ship's mission  "Free lunch" program initiated in NW China

"Free lunch" program initiated in NW China  Rime scenery in Mount Huangshan

Rime scenery in Mount Huangshan DPRK's Kaesong Industrial Complex

DPRK's Kaesong Industrial Complex 'Jin' named the word of the year

'Jin' named the word of the year Day|Week|Month