|

| A student uses a lathe to produce a component for his performing engineering operations qualification at Warwickshire College in the United Kingdom. [Photo / Provided to China Daily] |

Active, prudent steps needed to enhance skills of migrant workers

The road to sustainable urbanization in China depends largely on the structural shift from manufacturing-fueled growth to the development of a knowledge economy, for which education and training plays a central role.

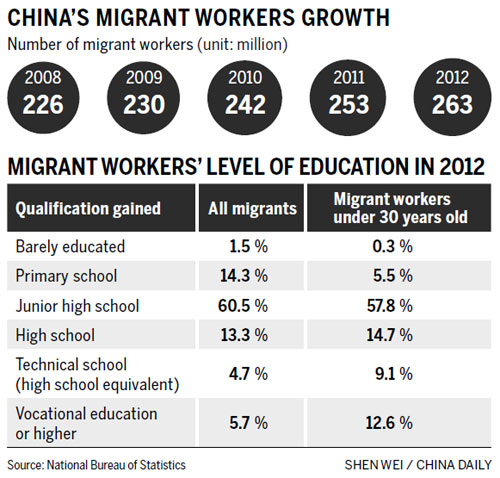

Across the country, migrant workers are flooding into city centers to provide an abundant labor pool. According to data provided by the National Bureau of Statistics, in 2012, China had about 262 million migrant workers, an increase of 37 million from 2008.

However, as China shifts gears to more high-tech and service industries, migrant workers will also need to upgrade their skills.

What makes this shift paramount is the fact that, even among young migrant Chinese workers under the age of 30, only 57.8 percent have been educated up to junior high school level (about 15 years old), according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

"Many younger migrant workers, commonly those born after 1980, aspire for an urban life. The one barrier they experience is the gap in skills between them and the urban population," says Zhan Changzhi, a vocational education expert from Hainan University.

"Most of the job vacancies in the cities are in factories and services industries and, as such, not many migrant workers are equipped with the skills to fill these roles. This is why vocational education has big potential in China," Zhan says.

According to Zhan, most urban jobs require highly skilled workers, because Chinese companies are gradually moving up the value chain. At the same time, improving living standards in cities also means urban people are now more demanding about the services they receive.

"In the past, migrant workers could go through a training process of 10 days to a fortnight before they were ready to start work, because they typically worked in jobs such as parcel deliveries on motorbikes, which require little skill," Zhan says.

"But nowadays, there are many posts in urban factories that demand highly skilled technicians, which means students need to undergo extensive training."

Despite an availability of vacancies in cities' services and high-tech sectors, vocational education providers are still finding it hard to recruit students because vocational education is seen in China as less respectful than university education, he says.

Wang Fengqin, a 17-year-old high school student from Wangmo, a remote county in Southwest China's Guizhou province, concurs with Zhan's observations.

"My mother wanted to send me to a technical school rather than high school, while the family elders insisted that I would have a better future after high school graduation," she says. Wang's mother, who is a migrant worker in coastal Zhejiang province, believes vocational education is more suitable for her daughter.

Several other students who are likely to end up as migrant workers also share Wang's dilemma.

Zhan says that most of the young people in China aspire to be a civil servant, whose average salary is about 4,000 yuan ($652) a month, much below the average salary of 8,000 yuan that some highly-skilled technicians can earn.

Hebei woman latest case of H7N9

Hebei woman latest case of H7N9

![]()