Zhang Yadong, vice president of the Zhejiang College of Sports, to which Sun is affiliated, talked about Sun being a sinner and of the punishment being for Sun's own good. Hearing Zhang's comments, you would think Sun was 11, not 21.

It's clear that Sun's advisors need to readdress the priorities in the young man's life. After all, without continued success in the pool, commercial opportunities will soon dry up. Taking the decision out of Sun's hands, as authorities have done by suspending him from competition, is only likely to alienate him further and push him to give up swimming altogether.

Zhang also compared Sun's indefinite suspension to that of speed skater Wang Meng who was banned for 400 days after a drunken brawl with her team manager. In no way should that kind of behavior be condoned, but there needs to be more of a balance between treating star athletes like children and allowing them a certain amount of freedom, especially once they have achieved their stated goal of winning medals.

It's also extremely hard to imagine that Sun will be suspended for anything close to 400 days. That is because the Chinese squad for the Asian Games will be announced in about 200 days, and it's safe to say that Sun's name will surely be on that list. Sun finished second to Korean star Park Tae-hwan in both the 200-meter and 400-meter freestyle events at the 2010 Asian Games in Guangzhou and he will not be denied the chance to reassert China's dominance over South Korea when the Games take place in Incheon next year. Not even for the sake of teaching him a lesson.

It is clear, though, that Sun needs a firmer hand to guide him than he's been getting up to this point, even if pushing him from one extreme into the other is not the answer. It has long been rumored that his mother is responsible for Sun's commercial schedule, but when he reportedly has to hand over two-thirds of everything he earns in endorsements to the China Swimming Association, it's understandable that he wants to lock down as many contracts as he can while still at the top of his game.

Unfortunately for him, sponsors will not be knocking down Sun's door after this latest episode. Potential brands will hardly be impressed that a pitchman for Hyundai has now been seen on the streets driving both a Porsche and an Audi, but not a Hyundai. But even if few tears will be shed if Sun's bank balance is a little less bloated next year, he remains one of the lucky few in China's sporting arena, a star who stands out even among his fellow Olympic champions.

For the majority of athletes in China, though, the future is looking less than rosy. The current system, in which athletes in state-run facilities are pushed to breaking point and then discarded once they have served their goals, is outdated. On a purely statistical basis, China's Olympic system has been very successful -- with a staggering 51 gold medals at the 2008 Olympics -- but at what cost?

Gymnast Yang Yilin admitted after winning three medals in Beijing that she did not even know if her parents had come to the capital to see her compete. Diver Wu Minxia was only told after winning a third straight gold in London that her grandparents had died and that her mother had been battling breast cancer for almost a decade.

Who decides if these children -- for they are extremely young when first set on the path to Olympic glory -- want to make these long-term sacrifices? And who is there to pick up the emotional pieces after their careers end?

Sun Yang may need to reform his ways, but the whole system needs reform as well.

<i>Mark Dreyer has 15 years experience in sports journalism and worked for Sky Sports, Fox Sports and AP Sports. He has covered the last three Olympic Games and has been based in China since 2007. He can be contacted at dreyermark@gmail.com

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of People's Daily Online</i>

Luxury-cars parade held in Dubai

Luxury-cars parade held in Dubai Special forces take tough training sessions

Special forces take tough training sessions Fire guts 22-storey Nigeria commercial building in Lagos

Fire guts 22-storey Nigeria commercial building in Lagos A girl takes care of paralyzed father for 10 years

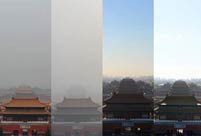

A girl takes care of paralyzed father for 10 years A record of Beijing air quality change

A record of Beijing air quality change In pictures: explosions occur in Taiyuan

In pictures: explosions occur in Taiyuan Live a harmonious life in Pu'er, SW China

Live a harmonious life in Pu'er, SW China Weekly Sports Photos

Weekly Sports Photos Gingko leaves turn brilliant golden yellow in Beijing

Gingko leaves turn brilliant golden yellow in Beijing Maritime counter-terrorism drill

Maritime counter-terrorism drill Loyal dog waits for master for six months

Loyal dog waits for master for six months The catwalk to the world of fashion

The catwalk to the world of fashion  China in autumn: Kingdom of red and golden

China in autumn: Kingdom of red and golden National Geographic Traveler Photo Contest

National Geographic Traveler Photo Contest Living in an urban village: 'Iron-digger' Xiong Sansan

Living in an urban village: 'Iron-digger' Xiong SansanDay|Week|Month