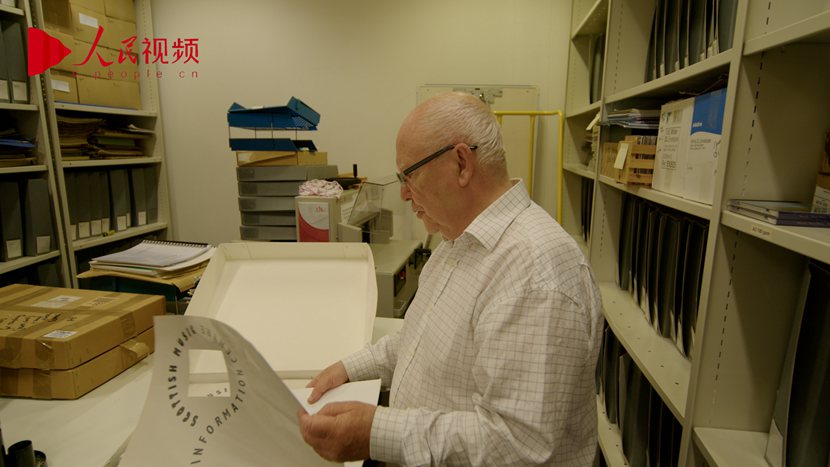

Edward McGuire: Exploring the meeting point of music of the East and the West

Midsummer, Glasgow. The Nelson Mandela International Day was celebrated here every year. At the memorial banquet held at the City Chamber this year, a world-music trio played miscellaneous tunes from different regions of the world. More unusual was that the widely-known Chinese folk tune, Moli Hua (Jasmin Flower) was also heard. And this was played by the leading flautist—the Glasgow-born Scottish composer and musician Edward McGuire.

McGuire represents a rare example of a contemporary British composer who has composed for the classical orchestral world and the folk music world—Scottish, Celtic, and Chinese—with equal passion and prolificacy. Over the past decades, McGuire has collaborated with numerous top-class orchestras and has been featured at many international music festivals. He received the British Composers Award and the Creative Scotland Award. As a valuable contrast to his classical music practice, McGuire’s flute playing made him the leading musician in two folk music bands: the Scottish Whistlebinkins and the Scotland-based Chinese Harmony Ensemble. His Chinese connection continues with a considerable number of classical compositions inspired by traditional Chinese music and culture.

Edward McGuire

Meeting China through music: Germination of a friendship

People’s Daily Online: You took The Whistlebinkies to Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou for an exchange tour with the Beijing Goodwill Folk Group in 1991. This was something quite exceptional. The Scotsman describes it as “our nation’s first musical representatives in the PRC”. Could you share with us some most memorable elements of your early encounter with China and its culture?

McGuire: I would say that my origin of performing and being interested in the traditional music of China goes back to my student’s day when I bought a flute for the first time, a bamboo flute, actually the xiao flute in 1968. My introduction to China was in November 1990, when I went to Hong Kong with the Scottish Ballet for my Peter Pan. Also, in Beijing, I met the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries, and they invited The Whistlebinkies to do an exchange visit with Mr. Zhou Yaokun’s traditional music group, the Goodwill, the following year. Mr. Zhou, the virtuosic erhu player, introduced me to some melodies that our folk music group should play when we did the music tour. Also, in Shanghai, I met Mr. Gu Guanren who was the director of the Shanghai National Music Orchestra. So that was a good introduction. We played some music together and then the tour was a very exciting one.

After coming back from China I started to study the Chinese language. One of my Chinese friends, a dancer and a choreographer, had the idea of bringing Scottish and resident Chinese musicians together in the formation of a group that would later become the Harmony Ensemble. I was playing the Western orchestral flute in The Whistlebinkies and I was playing the bamboo flute in the Harmony Ensemble. And in 2004 we got an award to produce a one-act ballet based on the old Chinese legend of the Ox Boy and the Weaver Girl. We had a real combination of traditional instruments including the Scottish bagpipes, concertina, the Celtic harp, and the Chinese yangqin, erhu, and guzheng, and I was playing the dizi. We created a combination of music styles from both countries, by, for example, using the idea of pentatonic melodies to bring the two sides together.

People’s Daily Online: You set an excellent example for us in terms of making music a powerful means for deepening the connection between nations and cultures. Your orchestral work Chinese Dances, for example, was used as encores by the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra on their China tours, and your ensemble piece Chinese Folksong Suite was played at the ceremony of the Confucius Institute at the University of Glasgow. What do you think is truly special about your practice in this regard?

McGuire: I learned a lot through talking, hearing discussions, listening and performing with local Chinese musicians. I did an arrangement of Three Chinese Dances, based on the traditional dance music of Yunnan, Xinjiang and Tibet. These very varied melodies are ones that Ms. Wu Yanmei introduced me to and she could sing some of those songs and also dance to them. And, interestingly, it was a classical music group that asked me to write that. So that was a very nice collaboration of dance, folk music and classical players. An American classical group, the Zodiac Trio, played the piece for their concert tour in China in 2013, including one at the Yantai Grand Theater. It had a successful reception. So it is an interesting phenomenon of Chinese music coming around the world to my country and then being taken back by an American group from Scotland over to China again. It just shows how music can be very part of the interchange of ideas and friendship between countries.

I also work with an organization called the Scotland China Association and they selected me to be vice president of that about 20 years ago. And I still do those functions for them. So we keep up an interest in what is happening in China and the role it has been playing globally. So we have a deeper understanding of the fact that there is a good role for culture to play in achieving peace and boosting communications between nations. That is a very important thing.

Edward McGuire

East and West: Dare to break boundaries

People’s Daily Online: Since the 20th century, Chinese musicians started to have the opportunities to have their voices to be heard worldwide. Composers Tan Dun and John Cage (with whom you have both befriended), for example, are well-known pupil-mentor duos that have had a huge influence on the West’s understanding of Chinese culture. What are some of your impressions of contemporary Chinese composers and musicians?

McGuire: I remember in 1988, there was a special festival called New Chinese Music in Glasgow, and that was organized by the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra. They invited several Chinese composers to have their pieces performed. Mike Newman was the producer. He went to China and met the composers. Mike brought them here, and one of them stayed here to work with the BBC Orchestra in Glasgow. And that man was Tan Dun, and he became the associate composer and conductor with the orchestra for three years. And I met him at that time. I had some pieces played by the orchestra in those years and we became friends. The very interesting thing is that he was translating some texts from John Cage, the Eastern-influenced American composer. He had also written, in Chinese, articles about John Cage. And those articles are important ones for the Chinese to bridge the philosophical gap between China and the West.

In 1990 The Whistlebinkies played John Cage’s 4’33’’ at the Musica Nova festival in the Concert Hall of the University of Glasgow. In the same concert, we premiered his Scottish Circus, which we had commissioned from him in 1985 after working on an improvisation with him one year before. At the Edinburgh International Festival that year, The Whistlebinkies gave an improvised performance, under Cage’s direction, at the reception for the opening of an exhibition of Cage’s visual artworks at the Fruitmarket Gallery. John Cage died shortly after composing Scottish Circus. I wrote his obituary, and then I was invited to the funeral memorial celebration in New York. And I went there and got in touch with Tan Dun, and he said, come and stay at my flat in Eastern Broadway. It was October 1993, I think. We talked a lot that evening, and we went out and looked at the big Halloween parade. I think Tan Dun has done a lot in terms of exploring the meeting point of the music cultures of the East and the West. He, for example, did field recordings of the very old traditional women singing of central China and incorporated them into his own works.

People’s Daily Online: You are familiar with Scottish, Celtic and Chinese traditional music, and your composition and music performance freely switch between different cultural traditions. Any thoughts to share with us regarding your experience of exploring the traditional culture of multiple origins?

McGuire: Cultures of the other provide us with very different ideas. In Chinese music, a single note can also mean a single gesture of a phrase of music. In Chinese painting and calligraphy, so much meaning was put into a minimal activity. And therefore we come to the inspiration that people who are interested in the philosophy of the East and China in particular, like John Cage, brought into their music some philosophical and meditative meaning. In terms of cross-over music practice, I think anyone interested in music should explore the contrasts and the meeting points of Western and Eastern cultures. One example of a similar meditation and stillness is created by the classical music of the Highland Bagpipes in Scotland, in which the evolution of the theme becomes a universe in itself. And the constancy of the drone of the bagpipes, if it is well in tune and well played, can have a transcendental or meditative or magical effect on the listener. We could also compare, for example, women’s folk singing of China with the traditional female singing of the British Isles, especially those that use the pentatonic scales.

I think, the quest to join, to allow the essence of traditional music to come through, not to copy traditional music, but to allow the inspiration, the rhythms and the instant communication between composer, musician and audience is a very important one. Through performing traditional music on the flute in The Whistlebinkies, I have learned how to instantly communicate with an audience and cause emotional conversations. I think contemporary music went through a period of very difficult communication which excluded a lot of people. So I would like to bring back the emotional connection in music, and I think we can be taught how to do that by observing how traditional music does that.

Edward McGuire

People’s Daily Online: In the era of globalization, artists enjoy great freedom in making their choice—they need to define themselves culturally between the East and the West, the traditional and the contemporary. What is your philosophy on this? Can you give some advice to young Chinese composers and musicians?

McGuire: For me, there is an interesting question about how traditional culture interacts with classical music and culture. I have a feeling that the impresarios of the world of entertainment and music and festivals sometimes cannot categorize me, because sometimes they think I’m a folk musician, sometimes they think I’m a modern classical musician. Other people think I’m too romantic or too traditional in my orchestral music. So I have a broad style that might not be easily categorized, but I think I can explain it to people and I set an example to other composers. I don’t teach them, but I think I try to set an example.

I think young composers should remain true to their human essence and try to communicate with people. Try to communicate with a wide audience. Try playing your music to your parents and grandparents and ask them what they think. That is one of the best thermometers for testing your musical temperature. And also, don’t forget the young children. Music for children is an amazing thing to try and do.

There is a very interesting question about, in modernism, how to deal with ancient cultures and how they influence what is looked upon as modern culture. Time is moving on every day, so anything that is called modern is old next week. So you cannot rely on modernism being around too long. And there are ancient cultures and traditions that really are part of the human being’s outlook, part of our bodies, of our souls and minds. So people still look for beauty; they look for rhythm; they look for pulses like the heartbeat and emotional statements. And that does not change. It is called being human.

Photos

Related Stories

- Feature: China Now Music Festival kicks off new season in New York City with "Tales from Beijing"

- Music traditions stoke artistic passion in China's ice city

- British singer combines Chinese elements with his music

- Video game CS:GO introduces first music kit in Chinese to celebrate 5th anniversary

- 'Post-95s' couple goes viral for Chinese dulcimer livestream performances

- Lang Lang performs in Ljubljana's summer moonlight night

- Chinese musicians turn landscape masterpiece into epic work of classical music

- Feature: 2nd edition of Montreux Jazz Festival China ready with aim to connect through music

- Orchestra in Henan revives ancient Chinese music

- Sacred Music Festival held in Athens

Copyright © 2022 People's Daily Online. All Rights Reserved.