'Asian NATO' perilous and unwanted for Asia

Illutration: Liu Rui/GT

--An "Asian NATO" will surely be equally NA(o)TO-rious and hazardous, both militarily and economically.

--For the Asia-Pacific region, an "Asian NATO," even in its embryonic form, will be destined to heighten military risks, create more turmoil, and risk draging the entire region into Washington's insatiable gambit for more geopolitical clout and hegemony.

In the early 1990s, when the Soviet Union was heading straight toward its sudden dissolution, leaders from NATO member states rushed to do their calculations. Should the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which had been built upon the premise of countering the Soviet superpower, also become history with the demise of its raison d'être? Some pondered. But still, a host of politicians from NATO member states cautioned against its abolishment and argued that, even after the Soviet Union collapsed, the need to "preserve the strategic balance in Europe" still remained. It was with the belief of swapping Europe's strategic autonomy with the ostensible "strategic balance" that NATO offered, a bygone concept from the Cold War-era reemerged and eventually widened its scope in a new century, and instead of shrinking or fading away it has instead expanded, incorporating more and more Central and Eastern European nations into its membership.

NATO, Asian edition?

NATO's ambition and appetite have never been just confined to the Trans-Atlantic, as hardly had the Iron Curtain ceased to exist when NATO began to involve itself in wars of regime-change and invasions into Iraq and Afghanistan. In recent years the Western military alliance has also been rising in strength at an alarming rate, spreading its tentacles further to reach regions in Asia. High-level officials from Japan, South Korea, India, and Australia (with the latter, strictly speaking, simply being a nation that happens to be adjacent to Asia), among others, all being non-NATO states, and have long been frequently invited to join NATO meetings (including the one that was held earlier this month), at which NATO has spared no efforts to exercise its "long-arm jurisdiction" over issues such as the Korean Peninsula nuclear issue.

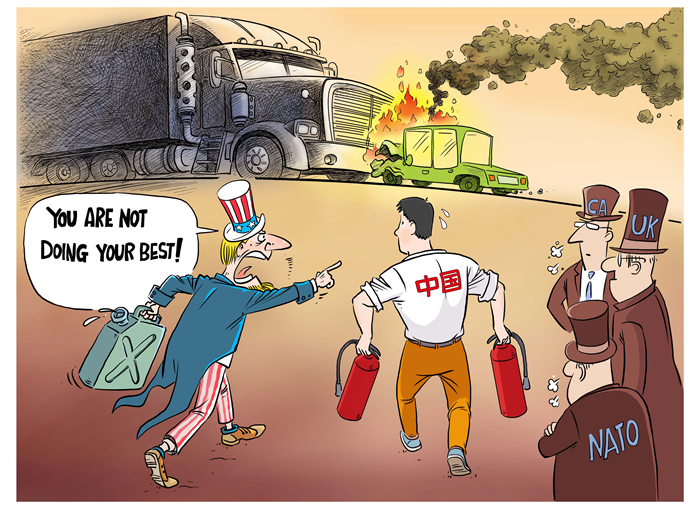

Since the simmering tension between Russia and Ukraine (the latter has been keen to join NATO despite the former's fierce objection) escalated into a deadly war, Washington, the de facto leader of NATO, has grown increasingly active in preaching about the alliance's significance. Not only have senior US officials turned their global visits into opportunities for the special promotion of NATO, but they have also repeatedly cited the so-called "China threat" and "Ukraine lesson" as excuses to urge military alliances in the Asia-Pacific region to be further cemented and bolstered. In a flurry of meetings and phone calls after the eruption of the Ukraine conflict, US president Joe Biden praised the "supportive" role of the Quad, an alliance between the US, India, Japan, and Australia, while reassuring the bloc's partners of Washington's commitment to supporting Australia with nuclear submarines and other advanced weaponry (such as hypersonic weapons) under AUKUS, a trilateral pact between the US, UK, and Australia.

Whatever intentions Washington may harbor—whether integrating more Asian nations into the already loaded roster of the NATO alliance, or duplicating and nurturing more NATO replica or quasi-NATO intergovernmental organizations around the world—they will surely be equally NA(o)TO-rious and hazardous, both militarily and economically.

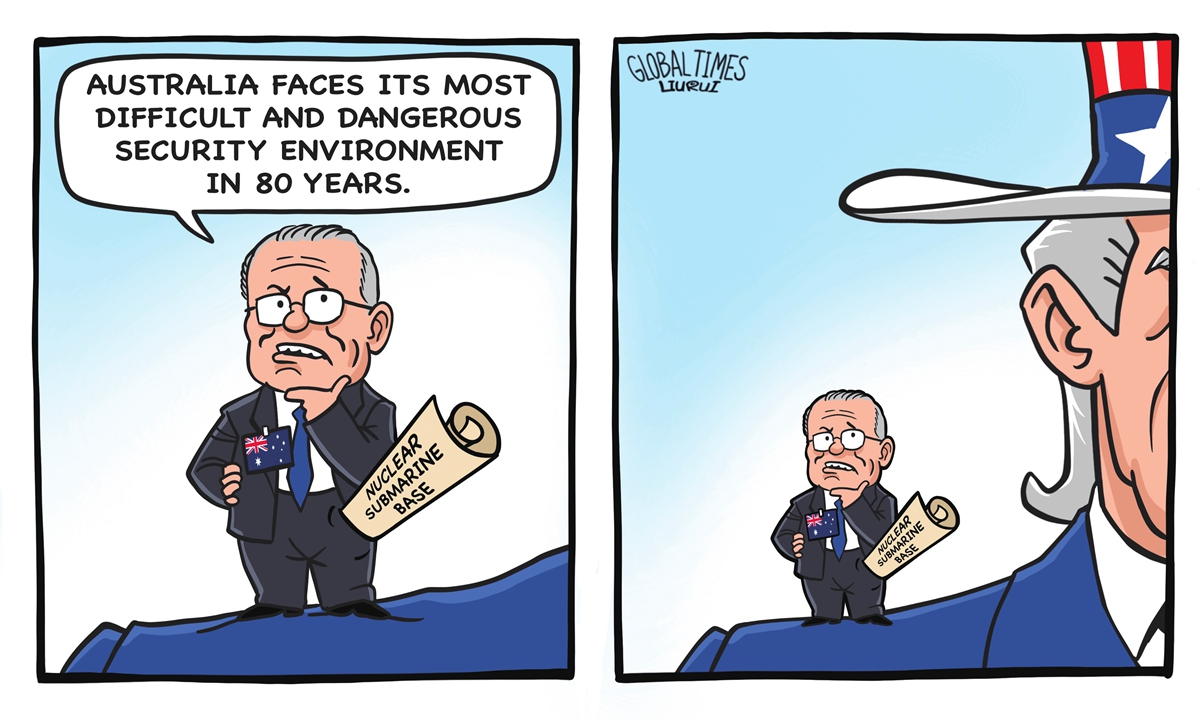

Cold War schemer Cartoon: Xu Zihe/GT

A security mirage

To begin with, Washington's attempts to build a NATO replica organization—or, as many are calling it, an "Asian NATO"—will only serve to sabotage regional security and stability instead of "promoting" these goals.

Through bilateral security treaties and multilateral defense alliances like the Quad and AUKUS, Washington has for years laboriously weaved its so called Indo-Pacific "collective defense web" into something akin to that of NATO, all at the expense of the common peace and stability shared by the entire region.

But the idea of seeking "collective security" through "collective defense" doesn't hold water because Washington's strategy by nature is hostile and "coercive," which is exactly what Barry Blechman has written and argued, an American scholar focusing on nuclear disarmament, in his 2020 book Military Coercion and US Foreign Policy.

Holding the banner of bloc politics and power politics, the US has relentlessly borrowed coercive and hegemonic tactics from its Cold War toolbox: stationing its omnipresent troops, deploying defensive systems, conducting joint naval exercises, and selling lethal weapons. All of these tactics, however, only serve to create a mirage of security, one that is parochial, unsustainable and can fail at any time (As Blechman pointed out, during the post-Cold War period US efforts to coerce other states failed as often as they succeeded).

Take the nuclear crisis on the Korean Peninsula as an example. Washington has always acted as the major player on the issue, and with its perilous moves, the US has sometimes grabbed the limelight away from even the ROK and DPRK themselves. In 2016, Washington announced that it would deploy THAAD, an anti-ballistic missile defense system, in South Korea, against vehement protests from countries within the region and from South Koreans. This omnipotent but unnecessary defense system was combined with a bombardment of sanctions and unrelenting joint military exercises. This shows that Washington has utilized every coercive device at its disposal despite the crisis having become even more convoluted and insoluble in recent years.

Washington's military presence in the region has not only given rise to on-and-off tensions on the Korean Peninsula, but the US army itself has also been muddling the otherwise pacific and stable state of the region. Its spy planes have continued hovering and buzzing over sensitive waters, its ships and vessels have continued cruising in an often provocative manner, and one of its nuclear submarines was met with a collision in the South China Sea.

Setting NATO as an exemplar, Washington is bent on constructing a hostile and turbulent climate, where any sense of security and stability is exclusive to only those nations living under its military umbrella. The ongoing Ukraine conflict has offered the world a wake-up call that NATO's eastern expansion and growing coercion is no solution for peace, on the contrary, it was only the prelude to a shattered peace and a disrupted "strategic balance" in Europe. This scenario is exactly what the nations in Asia should act to prevent. For the Asia-Pacific region, an "Asian NATO," even in its embryonic form, will be destined to heighten military risks, create more turmoil, and risk draging the entire region into Washington's insatiable gambit for geopolitical clout and hegemony.

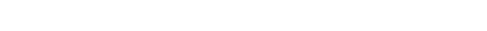

Australian doublespeak Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

A lose-lose trap

For years, China's peaceful rise and its dynamic trade ties with countries in Asia and beyond have become a thorn in Washington's side. Under the disguise of its "overarching" Indo-Pacific strategy, the US is utilizing military alliances to kidnap economic ties in the region, creating a lose-lose trap that no nation, except the US, wants to see.

The souring China-Australia relationship is the perfect case study of how Washington's bloc politics can take a toll on bilateral relations—and economic ties in particular—in the region of Asia and beyond.

China stands as Australia's largest trading partner, having imported approximately USD 164.8 billion worth of Australian goods last year, according to statistics released by the General Administration of Customs of China. By comparison, the US imported only around USD 12.5 billion worth of goods from Australia in 2021.

With Australia's trade axis leaning clearly towards one direction, Aussie leaders are still somehow convinced of the merits in shifting their foreign policies in another direction. Since the second half of 2020, Australia has joined Washington's call to smear China with baseless accusations, interfere in China's domestic affairs, and hype up the so-called "China threat," all against growing domestic concerns raised in Australia's frenzied anti-China rhetoric, stoked on by the US. This may fray the China-Australia relationship, one that Scott Morrison, Australian prime minister, has acknowledged as "valuable."

A possible Asian NATO may reflect part of Washington's efforts to resuscitate its "Pivot to Asia" strategy, but Asian nations' common interests have never revolved around the US: they remain deeply intertwined and deeply rooted in Asia.

Vibrant regional intergovernmental organizations in Asia like the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), together with promising free trade agreements, such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which consists of the 10 members in ASEAN, plus China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand, can serve as a strong indication that peace and development are still being prioritized and cherished and that multilateralism and cooperation can still prevail over bloc politics and confrontation.

(Cartoon by Ma Hongliang)

The world is not a land divided by different ideological lines or carved by different camps, awaiting Washington and the US military's alliances to conquer or deter enemies. In times of conflict and turmoil, we should all do more to cherish peace, a peace that is consolidated through common, comprehensive, cooperative, and sustainable security rather than sustained by pressure politics or Cold War-like power equilibriums. An "Asian NATO," by its nature, goes against the peace as we know it and will inevitably impair the stability and prosperity of the region. If anything, it is beneficial—only for its architect, the US itself.

Photos

Related Stories

- US claims of China’s nukes ‘excuse for own expansion’

- NATO urged to stop spreading provocative remarks against China: spokesperson

- (Poster) NATO is a danger to world peace. It must go: The Indian Express

- Unhealthy obsession

- Commentary: NATO should pivot away from China-bashing mania

- US, NATO seek united front with Asia-Pacific allies to isolate Russia, pressure China over Ukraine crisis

- AUKUS plans hypersonic weapons to confront China as US speeds up NATO, Asian allies' coordination

- 73rd anniv of NATO foundation a reminder of US long-term control of Europe’s security

- The changing attitude of NATO countries to accepting Ukraine refugees

- Experts: NATO's role worsens Ukraine crisis

Copyright © 2022 People's Daily Online. All Rights Reserved.