Cries for survival, justice -- overseas human rights survey (Part I)

-- The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that in 2011, the year the so-called "Arab Spring" began, the number of refugees arriving in Europe and dying in the Mediterranean topped 58,000 and 1,500 respectively, the highest level since 2006.

-- According to statistics, since 2001, the wars and military operations launched by the United States in the name of "anti-terrorism" have covered about 40 percent of the countries in the world, claiming more than 800,000 lives and displacing more than 38 million people. In Syria alone, by the end of 2020, 13.5 million people were forced to leave their homes, more than half of its population before the war.

-- According to the 2020 Annual Misery Index compiled by economist Steve H. Hanke of Johns Hopkins University, countries including Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Lebanon, Libya and Iran were among the countries with the greatest pressure to survive. The internal environment for peaceful development in these countries was often damaged by external interference.

Abdullah al-Kurdi holds a picture of his two sons who drowned in the Aegean Sea in Turkey six years ago, in Erbil, Iraq, Oct. 2, 2021. (Xinhua/Khalil Dawood)

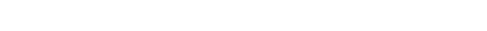

BAGHDAD, Dec. 12 (Xinhua) -- Living a life of contentment is the ultimate human right. According to a recent survey on overseas human rights conducted by Xinhua News Agency, nearly 70 percent of the respondents have a consensus that a sense of gain, security and happiness of the ordinary people is an important indicator of a country's human rights situation.

However, for many, because of the West's intervention, their primary basic human rights, namely the rights to subsistence and development, are still out of reach, while for some others, happiness is also a luxury.

RIGHTS TO SUBSISTENCE, DEVELOPMENT

"If Alan were still alive, he would be nine years old," Abdullah Kurdi, a 45-year-old Syrian refugee, murmured as he looked at his son's image in a painting.

On the wall of Kurdi's home in the northern Iraqi city of Erbil hangs a painting: a little mermaid swimming to rescue Alan as he lies facedown on the beach, no longer breathing.

In 2015, little Alan "sleeping" on the Mediterranean beach became one of the most heart-wrenching images of Europe's refugee crisis that year. Kurdi's elder son aged five and wife were also killed in the shipwreck.

Today, similar tragedies are still unfolding in some parts of the world.

After six years of war and displacement, survival and rebirth, Kurdi told Xinhua about the blood and tears of a refugee family.

On Sept. 2, 2015, a group of people in three cars arrived at a fishing village in the night off the coast of Bodrum, a city in southwest Turkey. Kurdi, his wife and two sons were among them. It was where they were going to sail across the Mediterranean to Greece.

At the time, as the Syrian crisis entered its fifth year, the situation became increasingly chaotic, lives were being destroyed by the fighting, and smuggling became a last resort for many.

It was not until the last moment that Kurdi found that what was waiting for them was not a speedboat as promised, but a humble boat that could not hold a few people.

"I refused to get on the boat, but the smugglers had guns. At this point it's either get on board or die," he remembered.

Kurdi knew that the road ahead would be dangerous, but he never thought it was really a road of no return.

The boat was so overloaded that it was overturned by huge waves just minutes after it set sail. Kurdi survived, but lost his wife Rehanna, his elder son Ghalib and his younger son Alan.

In that year, the total number of refugees who tried to cross the Mediterranean Sea to Europe like the Kurdi family exceeded 1 million, the vast majority from Syria.

Since the unrest in West Asia and North Africa in 2011, there has been a steady flow of refugees across Europe's borders from south to east.

From the south and southeast, a large number of refugees try to travel to Europe through the Mediterranean: either to Spain via Morocco and Algeria, to Italy via Tunisia and Libya, or to Greece via Turkey. But many never make it to the other side.

Uprooted people, many from war-torn countries in Asia and Africa, have been separated from their loved ones and have given up everything they have, like the Kurdi family, in the hopes of surviving.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that in 2011, the year the so-called "Arab Spring" began, the number of refugees arriving in Europe and dying in the Mediterranean topped 58,000 and 1,500 respectively, the highest level since 2006.

And this is just the beginning. As unrest continues in West Asia and North Africa, the refugee crisis is getting worse. From 2014 to 2019, more than 100,000 people were smuggled across the Mediterranean to Europe each year. More than 20,000 migrants died in the Mediterranean from 2014 to 2020. In the first half of 2021, 1,146 people died, 58 percent higher than the same period of last year.

Staying in Syria, they may die in war; crossing to Europe, they could die in the Mediterranean or somewhere else along the way -- that's the stark choice facing the Kurdi family and millions of people in Syria and other war-torn countries.

For anyone, if the right to subsistence is not guaranteed, all other rights are mere illusions. When Xinhua reporters talked to people in 10 Arab countries in the Middle East, including Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Egypt, about 70 percent of them told reporters they hope to "live better."

"Survival is the right of Syrians," said Adnan Hazim, spokesman of the Syrian office of the International Committee of the Red Cross.

"We are not just talking about Syrians, we are talking about humanity as a whole. This right must be enjoyed everywhere and at all times," he said.

THE WEST'S INTERVENTION

The Kurdi family had been living peacefully in the Syrian border town of Kobani. In 2011, the Syrian crisis broke out and the situation continued to deteriorate. Around 2013, Kurdi said, he noticed things were even more different because the Islamic State came.

"We could have died in Syria, too," Kurdi said. "My wife could have been captured, and my children and I could have been killed. Everyone knows what the Islamic State is like."

In 2003, the United States invaded Iraq, claiming the existence of weapons of mass destruction, and toppled Saddam Hussein. At the time, the Bush administration sought to replicate the American political model in Iraq with its so-called "Greater Middle East Initiative," but soon fell into a long-term confrontation with armed groups. The continuous war has provided a living space for al-Qaeda.

In 2011, the United States killed Osama bin Laden, the leader of al-Qaeda, in Pakistan, and then began to withdraw its troops hastily from Iraq. However, the chaos it left behind brought serious consequences, and extremist terrorist forces rose rapidly. At the same time, Syria was plunged into civil strife by the "Arab Spring" which was fomented by the United States and the West. The Iraqi branch of al-Qaeda took the opportunity to expand its influence into Syria and renamed itself the Islamic State, capturing territory in both countries and committing a lot of appalling atrocities.

According to Swiss historian Daniele Ganser, the extremist group Islamic State was actually "Made in America."

"Fear forces us to leave," Kurdi said, adding that it is also a choice many Syrian families have to make. Kurdi choked up several times and pressed his furrowed brow with hands as he sank into grief.

Six years later, Kurdi still blames himself for sending his wife and children to their doom. But he hated even more the intervention that had destroyed the peace and forced his family out of their homes.

A U.S. military vehicle runs past the Tal Tamr area in the countryside of Hasakah province, northeastern Syria, on Nov. 14, 2019. (Str/Xinhua)

"I don't understand politics ... but even an ordinary person knows that weapons enter Syria from Western countries, and intervention from the West is the root of the deterioration of the situation in Syria," he said.

Over the past years, the United States launched the Afghanistan War under the pretext of anti-terrorism, provoked the Iraq War by using a tube of white powder as evidence of Iraq's "chemical weapons," intervened in the Libyan conflict on the grounds of "humanitarian intervention" and launched airstrikes in Syria on the basis of fake videos staged by the White Helmets. The list goes on.

According to statistics, since 2001, the wars and military operations launched by the United States in the name of "anti-terrorism" have covered about 40 percent of the countries in the world, claiming more than 800,000 lives and displacing more than 38 million people. In Syria alone, by the end of 2020, 13.5 million people were forced to leave their homes, more than half of its population before the war.

Recently, in Eastern Europe, a large number of refugees from Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and other countries have been blocked at the borders of Belarus, Poland and Lithuania. As winter approaches, their fate is concerning.

It is the Western countries themselves that have caused the current migrant crisis, said Russian President Vladimir Putin, noting that the Western countries fought many years in Iraq and Afghanistan.

HOPE FOR PEACE, STABILITY

After the shipwreck in 2015, Kurdi buried his two children. For many nights after, he could not come out of the nightmare of shouting and searching for his children in the raging waves.

Kurdi has only one photo of little Alan and his brother. He found the photo in a news report and printed it out.

Taken in Istanbul in the summer of 2015, the photo shows little Alan holding his brother with his small hand, wearing a delicate bow tie and looking shyly at the camera.

Kurdi once thought his elder son Ghalib would become a doctor, and he hadn't even made any plans for Alan since he was too young. The fate of the family was changed by the war and destroyed by the shipwreck.

People should remember the tragedy to ensure that what happened is never repeated. "I do not want a tragedy, the same tragedy that happened to my children, to happen," Kurdi said.

When asked about their expectations for their future life, 43 percent of respondents from the Middle East chose "free from wars and conflicts," according to the recent survey by Xinhua on overseas human rights governance.

A displaced man and a boy are seen near a bombed site in a building complex under construction, where hundreds of displaced families live, in Tripoli, Libya, March 2, 2020. (Photo by Amru Salahuddien/Xinhua)

To realize this simple wish, peace and development are essential.

According to the 2020 Annual Misery Index compiled by economist Steve H. Hanke of Johns Hopkins University, countries including Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Lebanon, Libya and Iran were among the countries with the greatest pressure to survive. The internal environment for peaceful development in these countries was often damaged by external interference.

More than 52 percent and 30 percent of respondents of the recent survey believed "the role of autonomous and effective state governance in protecting human rights" is "extremely important" or "very important" respectively.

Rwanda is a convincing example. In the past decade and more, Rwanda's social and economic performance has been quite impressive in the economic reports issued by the World Bank and other relevant United Nations agencies.

Back in the 20th century, this African country was plagued by civil war and turmoil, and its people were living in poverty. In 2000, the country's President Paul Kagame found and established an independent development path that fit their national conditions, which led the country come out of the bottom and head into a period of rapid development, and improved people's livelihood.

Pursuing a happy life is the common aspiration of people of all countries. No matter how weak the foundation of a country is, as long as the environment is peaceful and stable, the right to independent development can be guaranteed, generating great potential.

Every Sept. 2, Kurdi delivers clothes and school bags to children in a nearby refugee camp. He often thought that if it hadn't been for the wars and the smuggling boat, Ghalib and Alan would still be at school.

Children like Alan were deprived of the rights to survival and development. It is Kurdi's wish and his goal for the rest of his life to free more children from suffering and hunger, and help them access education and health care.

During the interview, a two-year-old boy with a pacifier slipped into the living room, looking exactly like little Alan. Kurdi said that the baby was born after he started a new family, and he also named the baby Alan.

"This name bears my memory of the past, and also contains my hope for a new life," he said.

Photos

Related Stories

- Living a happy life is the primary human right

- Chinese people are enjoying better human rights: Chinese UN ambassador

- Xinjiang residents rebuke slanderous "forced labor" claims

- A Discovery Tour | Trailer

- Full Text: Pursuing Common Values of Humanity -- China's Approach to Democracy, Freedom and Human Rights

Copyright © 2021 People's Daily Online. All Rights Reserved.