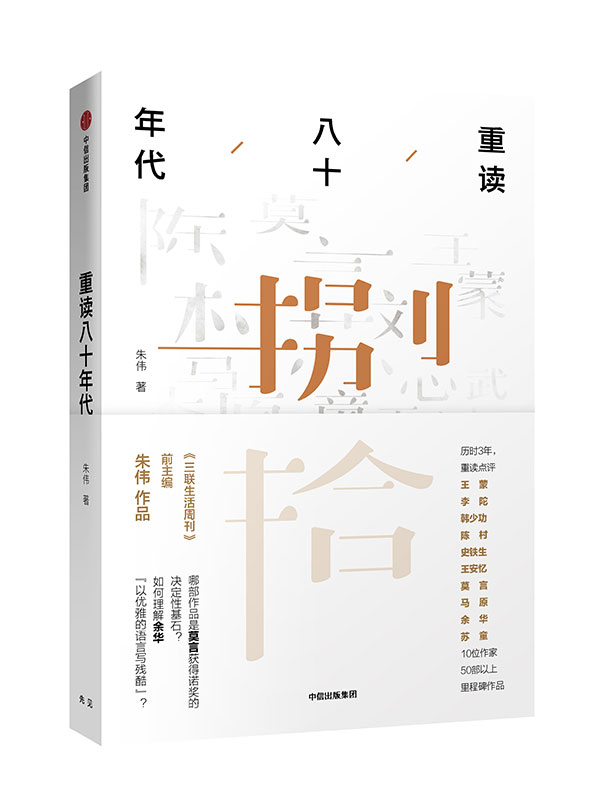

Chong Du Bashi Niandai (Reread the 1980s), by Zhu Wei. [Photo provided to China Daily]

After China's reform and opening-up began in the late 1970s, the following decade saw a burst of literary activity, with today's influential writers shaping their ideas and words back then.

In the preface of his new book, Chong Du Bashi Niandai (Reread the 1980s), literary critic Zhu Wei describes scenes from the decade in Beijing, saying that people would talk about literature all night long, or hang out like "lovers", walking from modern author Zhang Chengzhi's house to fellow writer Li Tuo's. And after eating watermelon under streetlamps, the people would walk along a city street to another author Zheng Wanlong's house.

Zhu also mentions that people watched rebroadcasts of World Cup soccer matches over drinks in the'80s.

From Franz Kafka and William Faulkner to Alain Robbe-Grillet, Juan Rulfo and Jorge Luis Borges, and from Jean-Paul Sartre to Martin Heidegger and Ludwig Wittgenstein-the discussions about the literary figures and their works were "like swallowing a date whole due to longtime hunger", Zhu writes.

"As Huang Ziping put it, as the writers were increasingly being 'chased by the dogs of innovation'. They were caught up in a race against time to try and absorb the diverse styles of Western literature."

During the '80s, Zhu, who was in his early 30s and an editor at China's top literature magazines-first China Youth and then People's Literature would ride his bike through Beijing's hutong (alleys), visiting one writer after another.

"The writers of that generation are successful today, which is largely due to that great period. ... People back then were very open-minded and intimate, so they understood and inspired one another," Zhu, now 66, says.

In the gold mine of contemporary Chinese literature in the 1980s, Zhu "dug out" important writers, such as Nobel laureate Mo Yan, Yu Hua, Su Tong, Ge Fei, Liu Suola and A Cheng, by publishing their first short stories in the magazines.

Zhu Wei, author [Photo provided to China Daily]

Although aspiring to become a top literature editor like American Maxwell Perkins, Zhu left People's Literature in 1995 and landed the position of editor-in-chief for the Lifeweek Magazine, an influential Chinese publication.

"People in People's Literature thought I wasn't suitable for the job of literature editor. Besides, the 1990s saw the gradual decline of literature and the rise of news media," Zhu says.

But his connection with literature was never severed. At Lifeweek Magazine, Zhu wrote a weekly column about novels. In 2013, he started writing a series of blogs online under the title The 80s and I to record his interactions with writer friends while keeping memories about his own early life alive.

After his retirement in 2015, Zhu started writing articles in the same magazine about authors in the '80s and his interpretations of their works after being invited to do so by its new chief editor.

"Compared with my interactions with them, I wanted to focus more on my interpretations of their works and their writing phases, which helps readers to better understand their works," Zhu says.

"Each writer is trying to give his or her answers to social problems. Each has their own stand. If you don't understand the background for their creativity, novels are just stories ... Once you attain their thoughts by learning about a writer's intention, your life is actually enriched."

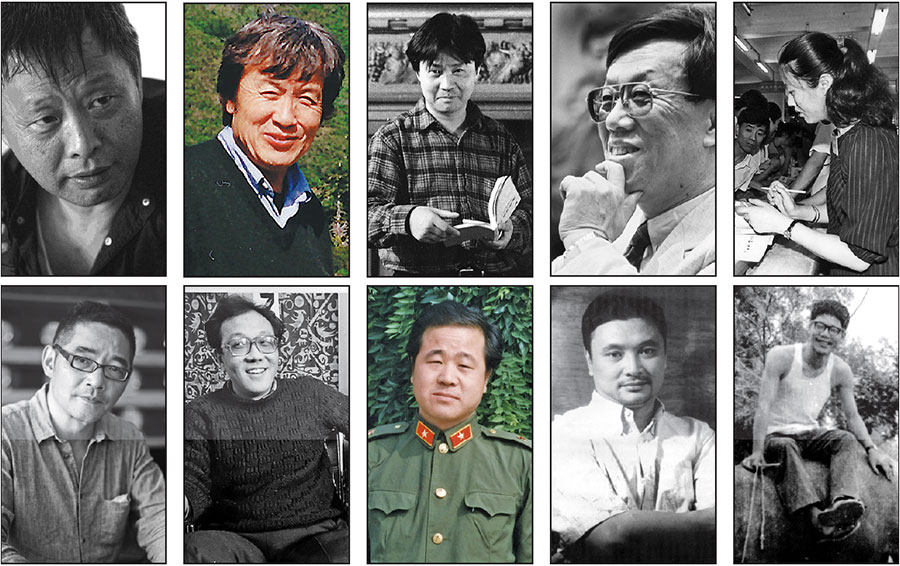

Zhu Wei’s new book, Chong Du Bashi Niandai, features 10 prominent contemporary authors: (clockwise from top left) Han Shaogong, Li Tuo, Yu Hua, Wang Meng, Wang Anyi, Chen Cun, Ma Yuan, Mo Yan, Shi Tiesheng and Su Tong. [Photo provided to China Daily]

In Chong Du Bashi Niandai, Zhu includes systematic interpretation of representative works by 10 prominent contemporary authors: Mo Yan, Wang Meng, Li Tuo, Han Shaogong, Chen Cun, Shi Tiesheng, Wang Anyi, Ma Yuan, Yu Hua and Su Tong.

While writing one piece on every author in his book, Zhu says, his main job was to read carefully all of their works. And while providing his interpretation of some details in their texts, he would ask the authors themselves if he wasn't so sure.

Ge Fei, a professor of Chinese literature at Tsinghu University and also a writer, says: "Zhu Wei was an impressive editor in the 1980s and one of the best literary critics in China, even back then. In Umberto Eco's words, he is a 'model reader', who can capture writers' intentions in the details hidden in the texts that are usually overlooked by most readers."

Ge, who has been Zhu's friend for 30 years, adds: "That is why he could befriend so many prominent writers."

One day Zhu sent him a message saying, "I am going to write about you," Ge says, adding that Zhu then asked him to mail all his works to him and told him to stay on call in case he had questions for Ge.

"It seemed unreasonable. I felt uncomfortable at first, but it's been his working style all these years-trying to do things as perfectly as possible."

Since he retired, Zhu has been working at least eight hours a day, reading or writing.

"I chose the 10 writers according to one standard-that is, whether they have provided a new writing style. There are some more writers that I haven't included in this book, but my next one will cover them, including Wang Shuo and Wang Xiaobo," Zhu says.

Award-winning photos show poverty reduction achievements in NE China's Jilin province

Award-winning photos show poverty reduction achievements in NE China's Jilin province People dance to greet advent of New Year in Ameiqituo Town, Guizhou

People dance to greet advent of New Year in Ameiqituo Town, Guizhou Fire brigade in Shanghai holds group wedding

Fire brigade in Shanghai holds group wedding Tourists enjoy ice sculptures in Datan Town, north China

Tourists enjoy ice sculptures in Datan Town, north China Sunset scenery of Dayan Pagoda in Xi'an

Sunset scenery of Dayan Pagoda in Xi'an Tourists have fun at scenic spot in Nanlong Town, NW China

Tourists have fun at scenic spot in Nanlong Town, NW China Harbin attracts tourists by making best use of ice in winter

Harbin attracts tourists by making best use of ice in winter In pics: FIS Alpine Ski Women's World Cup Slalom

In pics: FIS Alpine Ski Women's World Cup Slalom Black-necked cranes rest at reservoir in Lhunzhub County, Lhasa

Black-necked cranes rest at reservoir in Lhunzhub County, Lhasa China's FAST telescope will be available to foreign scientists in April

China's FAST telescope will be available to foreign scientists in April