One of the strictest countries in terms of gun control, China has seen many military enthusiasts unknowingly landing themselves in hot water for buying replica guns that are considered toys in other parts of the world but are seen as deadly weapons by the Chinese authorities. The strict firearm policy stems from a long history of weapon bans dating back to China's dynastic past, which remains deeply rooted in the authorities' anxiety toward social uprisings and how lax control of firearms may raise the cost of maintaining stability.

Police in Guangzhou display the guns they seized in a crackdown. Photo: CFP

Buying a toy gun may lead to life imprisonment in China but many people are not aware of it.

Liu Dawei, 20, thought it was a joke when he was questioned by police but later grew desperate when a court in Quanzhou, East China's Fujian Province ruled that 20 out of 24 of his replica guns, bought online from a Taiwan vendor and confiscated by mainland customs, were de-facto firearms and sentenced him to life imprisonment for weapon smuggling.

Liu felt the verdict could not be more ridiculous, arguing that the replica guns were merely toys with no ability to hurt people.

"Shoot me with my guns. I will plead guilty if they are capable of killing me!" Liu screamed in desperation at the judges when his verdict was announced last year.

His family was devastated.

His mother, Hu Guoji, burst into tears when Liu told his parents during their visits that he wanted to commit suicide.

"My son has always wanted to join the army. He started playing with plastic toy guns when he was three. He bought those replica guns to feel closer to his dream. Is this what he is supposed to get for wanting to defend his country?" Liu Dawei's father, Liu Xingzhong, told the Global Times.

To save their son, Liu's family has filed an appeal with the Fujian High People's Court. After waiting for more than a year, they finally received a notice two weeks ago saying that the court has started reviewing the case.

Liu was one of many people in China who, due to a lack of knowledge of the country's strict definition of firearms and rigid gun control policies, unknowingly made themselves criminals by trading or possessing what they believe are toy guns, which the authorities see as deadly weapons.

"China is one of the strictest countries in the world in terms of gun control regulations. There has been a historic tradition in this country, dating all the way back to Qin Dynasty (221BC -206BC), to ban the possession of weapons, which is deeply rooted in the authorities' anxiety and distrust toward what may come next if weapons are easily obtained by civilians," Ruan Qilin, a professor at the China University of Political Science and Law, told the Global Times.

Crime threshold lowered

China's Criminal Law, which was implemented in 1980, enforces severe punishment on the smuggling and illegal trade of firearms without providing a clear definition of what constitutes an illegal gun.

The punishment ranges from three years in jail for selling or buying one gun to life imprisonment or even the death sentence for dealing with more than 20 guns, according to Ruan.

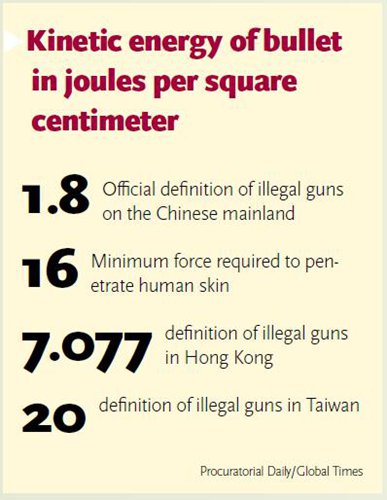

The current definition of firearms, which is widely adopted in courts across China, was created by the Ministry of Public Security in a 2010 document. It stipulates that guns that are able to fire bullets with a kinetic force of over 1.8 joules per square centimeter will be considered illegal firearms.

This new definition was based on a recommendatory industry standard made by a criminal technology committee in 2007, which was nine times more stringent than the previous one.

However, this criterion has been questioned by many scholars as a research report published in the Journal of Fujian Police College in 2008 showed that the minimum kinetic energy required to penetrate the human skin is 16 joules per square centimeter.

According to Zhou Yuzhong, a lawyer from the Yingke Law Firm who specializes in replica gun cases, the 1.8 joules per square centimeter threshold in the Chinese mainland is an 11th of the threshold used in Japan and Taiwan, and a quarter of the standard adopted by Hong Kong and Macao.

"By the 1.8 joules per square centimeter definition, the bullets can barely create a bruise on the human skin let alone shed any blood," Zhou said.

"Those who buy what were considered toy guns in Taiwan and Hong Kong will be charged with major felonies in the Chinese mainland. It looks almost like a farce," Zhou noted.

Zhou said his clients in gun cases come from all walks of life, including law enforcement staff such as police officers and judges.

One of his clients, Meng Qingwu, who served four years in a prison in Shenyang, Northeast China's Liaoning Province after selling seven replica guns in his toy shop in 2009, shared a cell with three prisoners on death row.

"It felt like a nightmare. One of my cellmates had killed four people and was still able to sleep soundly at night. I never quite understand how I deserved to be locked up in the same room with a bunch of murderers when all I did was play with toy guns," Meng said.

Lü Hongwu, a former judge from Jinhua, East China's Zhejiang Province who was sentenced to three years in prison with a three year reprieve for owning two BB guns, said the government has failed to notify the public of their 2010 change of policy.

"It came very suddenly when what used to be toy guns became defined as firearms. This includes rifles used in amusement parks to shoot balloons for prizes. If the Ministry of Public Security had broadcast it on TV or made public announcements in newspapers when they changed the criteria, people would oblige. But it did so quietly and many people became criminals without knowing it," he said.

Lack of legal support

Since the new definition was implemented, the number of gun cases has significantly increased.

According to data from the Ministry of Public Security, law enforcement officials busted over 9,000 cases involving making and selling guns from 2011 to 2015, arresting more than 80,000 people.

"In a lot of these cases, the so-called suspects had insisted that they had no idea that the 'toy guns' they purchased or sold are legally firearms. Therefore it is common for them to feel the verdicts are unjust," Chen Zhijun, a professor from the People's Public Security University of China, wrote in a paper published in the Journal of the National Prosecutors College.

He cited an example where up to 90 percent of the gun-related cases processed by Daxing district court in Beijing from 2010 to 2012 fell into the aforementioned category.

Chen admitted that the gun definition provided by the authorities falls far from public expectations and fails to keep a balance between maintaining social stability and safeguarding personal freedom.

"The replica gun cases usually have no victims. The suspects are either military enthusiasts or small businesspeople who have no intention to break the law," Zhou said.

Since 2011, Zhou has petitioned multiple times to the State Council and the National People's Congress (NPC) to abolish the current definition. Similar proposals were brought up at this year's two sessions by the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) member Zhu Zhengfu and NPC delegate Cai Xuefen, both of whom proposed that the standard be raised from 1.8 joule per square centimeter to 16.

"The current definition lacks legal support and is entirely based on an internal document of the Ministry of Public Security which has then based on industry standards. The core issue here is to prevent the administrative power of the police from meddling in legal affairs," Zhou told the Global Times.

He claimed that these cases often create judicial chaos and infringe upon citizens' rights and personal freedom.

"The ideological root of China's strict gun control policy is the long-existing gun-phobia in Chinese society. Inaccurate media reports that confuse replica guns with firearms and those that exaggerate the dangers of replica guns also contribute to the sentiment," Zhou said, adding that the government should differentiate different guns and recognize that the low-end ones are toys.

Zhou's opinion was echoed by Chen, who urged in his paper that China should carefully revise the current definition of firearms, especially for air rifles.

Ruan, on the other hand, defends the current criteria.

"Some of the rifles may not be able to deter the police force but can definitely scare off common citizens, which is not conducive to maintaining stability," Ruan said.

"It's not the definition or the criterion that created all the issues. The criterion will work better if the Criminal Law can be applied more flexibly," he noted.

Fire brigade in Shanghai holds group wedding

Fire brigade in Shanghai holds group wedding Tourists enjoy ice sculptures in Datan Town, north China

Tourists enjoy ice sculptures in Datan Town, north China Sunset scenery of Dayan Pagoda in Xi'an

Sunset scenery of Dayan Pagoda in Xi'an Tourists have fun at scenic spot in Nanlong Town, NW China

Tourists have fun at scenic spot in Nanlong Town, NW China Harbin attracts tourists by making best use of ice in winter

Harbin attracts tourists by making best use of ice in winter In pics: FIS Alpine Ski Women's World Cup Slalom

In pics: FIS Alpine Ski Women's World Cup Slalom Black-necked cranes rest at reservoir in Lhunzhub County, Lhasa

Black-necked cranes rest at reservoir in Lhunzhub County, Lhasa China's FAST telescope will be available to foreign scientists in April

China's FAST telescope will be available to foreign scientists in April "She power" plays indispensable role in poverty alleviation

"She power" plays indispensable role in poverty alleviation Top 10 world news events of People's Daily in 2020

Top 10 world news events of People's Daily in 2020 Top 10 China news events of People's Daily in 2020

Top 10 China news events of People's Daily in 2020 Top 10 media buzzwords of 2020

Top 10 media buzzwords of 2020 Year-ender:10 major tourism stories of 2020

Year-ender:10 major tourism stories of 2020 No interference in Venezuelan issues

No interference in Venezuelan issues

Biz prepares for trade spat

Biz prepares for trade spat

Broadcasting Continent

Broadcasting Continent Australia wins Chinese CEOs as US loses

Australia wins Chinese CEOs as US loses