Fifty years ago, more than 100,000 veterans from across China were shipped into the deserts of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region to provide the labor at the test sites for China's first atomic bombs. Since their retirement, the veterans, as well as some of their children, have fallen ill. But even though the Chinese government has granted benefits to some of them, some of the veterans are questioning whether the the government is doing enough.

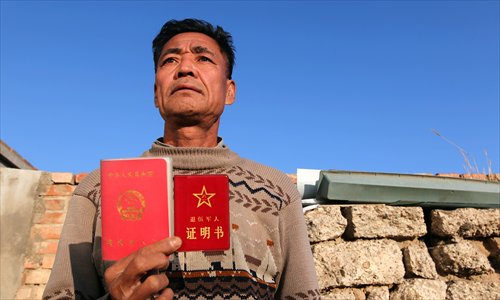

Su Chunchai, an atomic bomb-test veteran, holds up his retirement certificate and handicap certificate. Photo: Cui Meng/GT

The closest Ning Jiming has been to an exploding atomic bomb? A mere 5 kilometers.

The bomb was detonated underground, inside a hillside cave in Malan, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Ning heard a loud bang and saw the hill shake. He was wearing nothing more than his military uniform and a mask that covered his mouth.

As Ning watched the bomb explode, he was filled with pride. Little did he know the detonation was inaugurating a connection between his life and the bomb that would continue down to this day.

After retiring to Taonan, a city in Jilin Province, Ning and many of his peers found themselves developing all types of illnesses. Some even have affected their children. Ning's first son was born deaf. He had a second one in 1989, who was diagnosed with leukemia in 2011.

China detonated its first atomic bomb on the afternoon of October 16, 1964.

In the video footage taken at the site of the nuclear tests, there is a flash and a loud bang, followed by a mushroom cloud rising from the ground. According to Southern Metropolis Daily, those present jumped up, threw their hats on the ground and shouted "Long live Chairman Mao!"

In the 32 years following China's first A-bomb test, 45 bombs were detonated in Malan. More than 100,000 veterans, recruited from all over China, participated in such experiments in total, many of whom are now in the same sitatuion as Ning.

In recent years, the government has begun offering the veterans welfare benefits. But many are still not covered or are seeking higher compensation.

Ning Jiming's wife shows his son's legs, shrunken from leukemia. Photo: Cui Meng/GT

Memories of Malan

Ning knew many others working on the tests with him. The veterans were recruited in groups, many from neighboring villages in Jilin Province. Most were under 20, and the youngest, Zhao Dawei, was only 15.

Before going to Malan, Ning said, they were told they will be carrying out an experiment, but that was all.

After 12 days on a train, the veterans finally arrived somewhere much different than what they had expected.

The test sites were sandy and desolate. No living thing grew, no grass, the veterans remembered. The only living things were the veterans themselves, and the animals transported in to test the bomb's power, said Zhao Dawei.

As soon as they entered the site, they were informed of its purpose and sworn to secrecy.

"We were told not to mention the project to anyone. If anyone asked, we were working at Yonghong, a cement factory," Ning said.

This code name stayed with them throughout the duration. When they called or wrote to family, they couldn't mention anything about their mission; their letters were checked. There were also punishments if news leaked.

Ning often thinks back to those days. Getting used to the bad weather was the first obstacle. They faced nothing but sand, slept in camps, facing endless winds and temperatures as cold as minus 30 C.

Ning Jiming and his classmates weren't in the first wave of veterans at the site. He joined the military in 1977 and served at the site for three months.

His job consisted of going into the site, digging up dirt and covering the holes left by the explosion, to prepare the site for the next denotations.

Most of the veterans had specific small tasks, like Ning. They were told to keep their service secret, even long after it was over

Most of the jobs were trivial: digging holes, retrieving machinery, providing electricity. But the veterans endured because they were ordered to do so.

"But if you asked us again, not only Malan, even if it's somewhere worse than Malan, we'd go, there's no other choice," said Gu Xueqian, a 57-year-old veteran.

Ning Jiming cries over his son's hospital bed.Photo: Cui Meng/GT

Souvenirs of the past

At the time of the experiment, nobody knew what "nuclear" meant, let alone knew anything about radiation.

Ning now talks about radiation with the fluency of an expert.

"It's all something you can't see or touch, it's all in the air, as soon as you breathe in the air, you've got it in you," he said.

Now looking back, Ning said nobody had any special protection on, only uniforms, or at most a simple medical mask. The country was too poor at that stage to provide anything, he said.

After retiring from the military, many of these veterans went back to their hometowns. Many started showing symptoms of sickness, some quite quickly.

Gu started to develop spots on his leg soon after his retirement. In the following years, the spots developed into a skin condition, in which his entire leg turned black and he could hardly walk.

"It's as good as a dead leg," he said.

He went to the hospital, but the doctor couldn't say what caused the condition.

Zhao had another nameless condition. He has lumps all over his body, on his arm, legs, even on his scalp. The lumps sometimes ache. All he can do is take drugs to ease the pain.

Furthermore, sicknesses appeared among their children.

Zhao Dawei's son died at 8 from leukemia. He then had a daughter diagnosed with purpura, a blood disorder that causes purple-colored spots and patches to show on the skin.

When his second son got sick, Ning started wondering whether his children's illness were associated with his exposure to radiation.

"If I knew this was going to happen, I wouldn't have had the second son for sure," Ning said.

These veterans believe it's no coincidence their children are sick. But right now, in the medical field, there isn't a clear consensus on correlation between nuclear radiation and offspring's illness.

According to a study by the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the likelihood of cancer occurring after radiation exposure is about five times greater than a genetic effect (increased still births, congenital abnormalities, infant mortality, childhood mortality, and decreased birth weight).

The study also stated that "although radiation-induced genetic effects have been observed in laboratory animals, no evidence of genetic effects has been observed among the children born to atomic bomb survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki."

Ma Ji, the secretary of a soldier's reunion group in Taonan, said that out of 200 veterans in the area, there are eight children who have leukemia, a rate much higher than the natural occurrence rate of the disease, which is three in 100,000 people, giving them reason to believe it was no coincidence.

"Over 90 percent of the veterans themselves have different kinds of sicknesses. Many have died from cancer. Right now, only about 170 veterans are left in Taonan," he said.

Seeking better treatment

Ma has led the Taonan veterans on a few trips to raise awareness of the group, as well as asking for better compensation.

Starting in 2007, the ministries of civil affairs, finance, health, human resources and social security jointly released a series of documents giving benefits to the veterans, including disability evaluations, medical insurance and labor insurance.

The document stated that local health departments should help coordinate medical checks for retired atomic bomb test veterans and evaluate their handicap level. Those who were not evaluated as handicapped are given 40 to 100 yuan ($6.39-16) a month in compensation, varying from province to province.

The gesture was seen as a blow against the taboo and secrecy surrounding the subject.

But the veterans aren't entirely satisfied with the way the policies were carried out, especially since implementation differs depending on location.

"Some of the veterans have diseases, such as skin conditions, but weren't evaluated as handicapped veterans after medical examinations in designated hospitals," Ma said.

The veterans' assessed disability levels are directly associated with the amount of compensation they receive per month. Ma personally took a few to the Jilin provincial Bureau of Civil Affairs to argue their case.

Furthermore, where the veterans' children are concerned, China has only one national regulation covering financial assistance to those born with disabilities, and nothing about those who develop diseases later on.

Ning has spent more than 2 million yuan on his second son. He had to sell his house and land in his village, he said.

Ma said he has talked with veterans in other cities, such in Pinggu District, Beijing, who didn't even know that compensation policies existed.

Wang Keding, Zhu Huanjin and Gao Lianke, three former military scientists who were at the base in Malan, have written a letter that circulated the Internet, asking the government to raise compensation for the veterans. The letter states that the current level of compensation is "not scientific" and asked for one-time compensation of 100,000 yuan per person, as well as loosening the disability evaluation standard for the veterans.

Zhu said that since they wrote the letter, he thinks policies for disability evaluations have been loosened in Jiangsu Province. But he added that other provinces might implement the policies differently.

But right now, there isn't much discussion on the matter, nor signs of any change happening soon.

Ning spends most of his time in his son's room in the hospital. He hopes for a policy change, or at least for reimbursement from medical insurance, but it's a faint hope at best.

Day|Week

Breathtaking buildings of W. Sichuan Plateau

Breathtaking buildings of W. Sichuan Plateau Graduation photos of "legal beauties"

Graduation photos of "legal beauties" Top 10 most expensive restaurants in Beijing in 2015

Top 10 most expensive restaurants in Beijing in 2015 Special police force conducts multi-subject training in Urumqi

Special police force conducts multi-subject training in Urumqi 'Floating girls' in cheongsam

'Floating girls' in cheongsam Mysterious crater discovered in central China’s Hubei

Mysterious crater discovered in central China’s Hubei 630 monks walk for charity in Hangzhou

630 monks walk for charity in Hangzhou Glaciers on Qilian Mountains shrink 36 square km over 10 yrs

Glaciers on Qilian Mountains shrink 36 square km over 10 yrs